|

"A Sanctaury For Sokar" first appeared

in Appendix IV of Secret Chamber by Robert Bauval

Click on any picture to view larger

version.

As has been shown in previous books[1] the area known to the

Ancient Egyptians as Rostau (or Rosetau) is the place we now

know as Giza[2] and the deity associated with the environs of

Rostau (by the Old Kingdom) was Osiris. One important fact that

we know about the worship of Osiris was that in Archaic times

(first and second dynasties), and indeed up until about the

fourth dynasty, Osiris seems to have been nothing more than

an agricultural deity, possibly a corn god, as can be seen from

his later association with the colour green, standing for growth

and fertility.[3] It wasn't until Osiris usurped the role of

the god, Sokar, that he became associated with the realm of

the dead. However, for now we will concentrate on Osiris, moving

on to Sokar shortly. At the early mortuary complex of Abydos,

in lower middle Egypt, Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom pilgrims

would journey to leave offerings and Ushabti figures at the

site of the so-called hill of Heqreshu, close to the tomb of

the first dynasty king Djer,[4] for they believed this place

to be the tomb of Osiris. Petrie commented on this:

"At that time , with the revived interest in the kings'

tombs, this rise (i.e. the hill of Heqreshu) became venerated

: very possibly the ruins of the mastaba of Emzaza (on the

hill) were mistaken for a royal tomb. It was the custom

for persons buried elsewhere - probably at Thebes - to send

down a very fine ushabti to be buried here, often accompanied

by bronze models of yokes and baskets and hoes for the ushabti

to work in the kingdom of Osiris" [5]

As has been stated previously, in the archaeological season

1906/7, Sir William Flinders Petrie was digging in the desert

between Giza and Zawiyet el-Aryan, about two kilometres south

of the plateau, when he discovered a hoard of Ushabti figures.

The exact spot is hard to pinpoint as Petrie only states that

he found the figures in the plain beyond a rocky ridge that

rose half a mile south of the Great Pyramid,[6] the Ushabti

figures were found in pits about ten feet deep that were filled

with sand and rubbish. To all intents and purposes, these figures

were what are known as extrasepulchral Ushabtis, in other words,

they were left by pilgrims who were unrelated to any original

tomb or burial, many of these extrasepulchral were also found

by Mariette in the Serapeum at Saqqara, many of them bull headed.[7]

More of these figures were excavated in 1919 by an antiquities

inspector called Tewfik Boulos, on a small hill about six kilometres

south of the Petrie find. Some of the Ushabtis found by Petrie

belonged to an individual called Khamwase, a son of Ramesses

II, at the spot Petrie found no tomb as such, but he did find

some limestone building blocks that he couldn't explain.[8]

Why were the extrasepulchral Ushabtis left at Giza? Is there

a correlation between these figures and the extrasepulchral

finds at Abydos?

Was there a 'tomb of Osiris' at Giza/Rostau?

To answer these questions we must take a closer look at the

deity that predates even Osiris and whom Osiris actually assimilates

in the late Old Kingdom, that deity is Sokar.

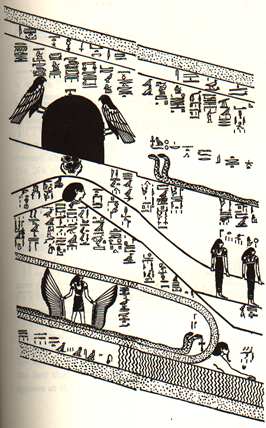

The

falcon headed deity, Sokar, has gained popular notoriety because

of his place in the fourth and fifth hours (or houses) of the

duat. Many researchers and authors have assumed that this figure

is just another side of Osiris and have therefore ignored him

altogether. Sokar however, merits closer attention. In my opinion,

Sokar could possibly be the oldest deity known in Egypt, far

older than Osiris and responsible for many of the later god

figures of dynastic times. Sadly, textural and archaeological

evidence for the cult of Sokar is sparse but from what we have,

we can piece together a picture of how the deity was revered

and worshipped not only in archaic and dynastic Egypt, but quite

probably pre-dynastic times also. By the time of the new kingdom,

the cult of Sokar, who it seems was a god of the Memphite necropolis,

had appropriated many of the ritual, mythological, and ideological

elements of the cult of Osiris.[9] But who was Sokar? The

falcon headed deity, Sokar, has gained popular notoriety because

of his place in the fourth and fifth hours (or houses) of the

duat. Many researchers and authors have assumed that this figure

is just another side of Osiris and have therefore ignored him

altogether. Sokar however, merits closer attention. In my opinion,

Sokar could possibly be the oldest deity known in Egypt, far

older than Osiris and responsible for many of the later god

figures of dynastic times. Sadly, textural and archaeological

evidence for the cult of Sokar is sparse but from what we have,

we can piece together a picture of how the deity was revered

and worshipped not only in archaic and dynastic Egypt, but quite

probably pre-dynastic times also. By the time of the new kingdom,

the cult of Sokar, who it seems was a god of the Memphite necropolis,

had appropriated many of the ritual, mythological, and ideological

elements of the cult of Osiris.[9] But who was Sokar?

There is no doubt that Sokar was originally a god of the Memphite

necropolis, indeed his name is echoed in the place today called

Saqqara and his sanctuary was at Rostau, which as we shall demonstrate,

was at south Giza and at which certain parts of his festival

were held. The primary objects of his cult were a mound and

his sacred boat called, the Henu-barque, it is the Henu-barque

that carries the dead king to heaven.[10] During the Old Kingdom,

Sokar is seen as a patron of craftsmen, specifically of metal

workers and in the book of the Am-Duat, Sokar inhabits a strange

land of the dead, a land that even Ra has no access to. This

fact alone attests to his importance. Sokar can be seen in the

representations of the fourth and fifth hours of the Duat, standing

upon his mound within what seems to be a hill topped by a black

conical symbol of some sort, possibly a stone.[11] In this place

the barque of the sun god, Ra, assumes the form of a snake in

order to crawl along the sand and so traverse the realm of Sokar

safely, whilst the souls of the dead cry out from the darkness

around him. This echoes the Henu-barque of Sokar, which also

is pulled along the ground and is placed atop a sled. The realm

of Sokar is guarded by the two Aker lions and by a plethora

of snakes and strange deities. The realm of Sokar certainly

qualifies as a 'secret chamber', so secret in fact, that as

we have noted, the sun god himself is denied access. It is interesting

to note here that an unnamed official of Pepi I was known as

'master of secrets of the chamber of Sokar'.[12]

Having ascertained that the character of Osiris in the context

of the late Old Kingdom texts (i.e. as a god of the dead), was

based upon and assimilated with the earlier god Sokar, where

does this leave us? Firstly, we must re-evaluate the idea that

we stated previously of a tomb of Osiris at Giza mirroring the

tomb of Osiris at Abydos. Surely, our references must now be

to the tomb, (or Shetayet as it is known from the texts) of

Sokar and the knock on effect of this is that the Abydos pilgrimage

site becomes the secondary site and the Giza site, the primary.

In other words, the archetype. Sokar is also assimilated with

the Memphite god Ptah by the time of the Old Kingdom and it

would seem that his assimilation had been going on for some

time. Further evidence of his assimilation with Osiris can be

seen in certain similarities between some of the ceremonies

enacted in Sokar's festival and some episodes in the Khoiak

festival of Osiris at Abydos.[13] As we have seen the character

of Sokar is intimately associated with his Henu-barque, possibly

echoed by the various boat burials found within the pyramid

fields.[14] In the festival of Sokar, besides the circumambulation

of the walls of Memphis, there was at some point in the ten

day festival, ceremonies at a Sokar-Osiris tomb, known as the

Shetayet, in the Memphite necropolis, specifically at Rostau.[15]

The French Egyptologist, C.M. Zivie, believes that Rostau is

located in the region of Gebel Gibli, about half a mile south

of the Great Pyramid and the site of the so-called southern

hill at Giza, this prominent hill is the only point on the plateau

that all nine pyramids can be seen from, it is interesting to

note therefore concerning this area, that Petrie found:

"many pieces of red granite, and some other stones

scattered about the west side of the rocky ridge, as if

some costly building had existed in this region."

[16]

This would place a possible structure just to the west of the

southern hill, in direct line with a most intriguing feature

of the plateau, the Wall of the Crow. Could it be that Howard

Vyse was right in thinking that the wall was indeed a causeway,

leading from an as yet, undiscovered structure?[17] If not a

causeway, then maybe an enclosure wall for the Shetayet of Sokar

and the Henu-barque sanctuary. Egyptologist Mark Lehner has

stated that the Wall of the Crow is quite possibly the oldest

structure on the plateau[18] and a close inspection of this

feature reveals it to be of cyclopean construction, with huge

blocks used in the body of the wall and three truly enormous

limestone blocks used to form the roof of the tunnel that runs

through it from north to south (or visa versa). It is also interesting

to note that the name Rostau was applied to an ancient village,

later known as Busiris, which stood approximately on the site

of the modern village of Nazlet-Batran.[19] It was in the desert

to the west of this village that Petrie found the extrasepulchral

Ushabtis mentioned above. It is tempting to speculate that these

pieces of granite could have belonged to the

Henu-barque sanctuary of Sokar, if this were the case, then

the tomb of Sokar (Osiris) could not be far away, as we have

previously stated, this tomb was known in the festival of Sokar

as, the Shetayet. The eminent British Egyptologist, I.E.S. Edwards

states that the Shetayet must have been a separate edifice,

though undoubtedly close to the sanctuary of the Henu-barque.

So,

lets review the situation, we have ascertained that an original

tomb of Osiris would be seen as a very sacred and mysterious

place, with pilgrims venerating and leaving offerings at the

site, that it is very probable that such a tomb did exist at

Giza and that this tomb was originally known as the Shetayet

of Sokar and was therefore the original and archetypal tomb

in Egypt, predating the tomb at Abydos. We have also pointed

out that Rostau was located at Giza and specifically in an area

known as Gebel Gibli, that the remains of a substantial and

costly building has been found in this area and that pilgrims

from at least the time of Ramesses II left Ushabti figures here

as offerings. Could it be that the way we see the Giza plateau

today is only three quarters complete? Was an ancient structure

in place in the area of the main wadi and the southern hill? So,

lets review the situation, we have ascertained that an original

tomb of Osiris would be seen as a very sacred and mysterious

place, with pilgrims venerating and leaving offerings at the

site, that it is very probable that such a tomb did exist at

Giza and that this tomb was originally known as the Shetayet

of Sokar and was therefore the original and archetypal tomb

in Egypt, predating the tomb at Abydos. We have also pointed

out that Rostau was located at Giza and specifically in an area

known as Gebel Gibli, that the remains of a substantial and

costly building has been found in this area and that pilgrims

from at least the time of Ramesses II left Ushabti figures here

as offerings. Could it be that the way we see the Giza plateau

today is only three quarters complete? Was an ancient structure

in place in the area of the main wadi and the southern hill?

Did the Wall of the Crow form part of this structure?

Standing between the fore paws of the brooding Sphinx of Giza,

the Dream Stele of Thutmose IV is largely disregarded by most

visitors to this amazing place. Approximately seven feet tall

and about three feet wide, originally a granite door lintel

from the mortuary temple of Khafre, the stone was used to commemorate

a special event in the life of a young prince.

The young prince Thutmose had been out hunting in his favourite

location, a place we know as Giza. Whilst out with his companions,

he decided to rest awhile in the scorching sun, beneath the

Sphinx, which was at this time buried up to its neck in sand.

As soon as the young prince had fallen asleep the Sphinx, in

the form of Hor-em-akhet, spoke to him in his dream. He proclaimed

that if Thutmose cleared the sand from his body, he would make

the prince a king.

He was true to his word.

The most telling part of the tale comes half way through. It

describes the area where Thutmose is resting as the 'Setepet',

or the sanctuary of Hor-em-akhet, which he details as being

'beside Sokar in Rostau'. Sokar, as we have seen is an early

Egyptian god of the dead and an integral figure to our whole

quest for the 'secret chamber', Rostau, again as we have pointed

out, being the ancient name of the Giza Plateau. Thus, the Stele

intimates that the Setepet, or the sanctuary of the Sphinx,

was 'beside' Sokar, but where? The next few lines of the stele

hold the answer.

The text describes the goddess Neith as 'mistress of the southern

wall'. Again, we are being given geographical references to

what can only be the Wall of the Crow. It continues: 'Sekhmet,

presiding over the mountain, the splendid place of the beginning

of time'.[20] Could it be that the 'mountain' was in fact our

southern rocky hill? Was this 'the splendid place of the beginning

of time'? And what was meant by 'beginning of time'? It is also

interesting that it is the goddess Sekhmet that 'presides over

the mountain', as in the various eighteenth dynasty tomb depictions

of the fourth and fifth hours of the duat, it is a female figure

that seems to encompass the hill of Sokar. Again we can see

clues that are pointing to a specific geographical location,

this location is southern Giza, around the rocky knoll above

the two modern cemeteries (one Muslim, one Coptic), just to

the south of the Sphinx.[21]

As well as the straight archaeological and historical research

that points to a hidden location on the plateau, I have, along

with my co-authors David Ritchie and Jacqueline Pegg put forward

two further arguments that are just as compelling, if not more

so. These revolve around the use of sacred geometry and astronomy.

The astronomical argument is too long and complex to enter into

in this short space, but I will let my co-author, David Ritchie,

introduce you to the geometrical argument we hope to bring forth

some time in the future.

There is one truth that still remains, it endures

even though Man has done his best to obliterate and destroy

it, because it's language humbled even the greatest conquerors.

I'm talking about the mathematics of the Giza Pyramids.

The only language which can not be corrupted, wherever,

or whenever, you are. Mathematics was the original language

of nature and the only way the Pyramid Builders could

send the message they so desperately wanted us to find,

the location of Sokar, in , "The Splendid Place of the

Beginning of Time".

The Giza Pyramids serve one ultimate purpose, to indicate

the Gateway to the Underworld by pure geometry. The number

system that is encoded in the dimensions and positions

of the pyramids of Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, their satellites,

temples and enclosure walls, form a geometrical picture

that ties together the geometries of the pentagon,

hexagon and heptagon, in other words, five, six and seven.

Sacred geometry was the fundamental of Egyptian mathematics,

the hieroglyphic symbol for the Duat is a five pointed

star enclosed within a circle. The "hidden circles of

the Duat" and the constructs that can be formed within

them comprise "the many paths of Rostau".

'Rostau'

is a four thousand cubit diameter circle and square centered

on the Great Pyramid. 'Sokar' (the names we have given

these constructs) is another, interlocking, 4000 cubit

diameter circle and square that creates a "Vesica Piscis",

or the "Eye of Horus". Together they comprise the Duat

. The center of this second circle is a very precise location

, exactly 800 royal cubits south of the north east corner

of the Sphinx temple. It is at the base of the vertical

northern face of a hill called Gebel Gibli, this hill

we believe to be the original "mound of creation". The

"Wall of the Crow", or "Southern Causeway", leads to this

place. The measurements from this point offer absolute

conclusive proof that there is something to be found beneath

the sand and debris that has accumulated at the base of

the hill over several millennia. The Giza pyramids form

a mnemonic computer, where the placement of every structure

indicates the next step to be taken in a sequence that

harmonizes and integrates the different geometrys. 'Rostau'

is a four thousand cubit diameter circle and square centered

on the Great Pyramid. 'Sokar' (the names we have given

these constructs) is another, interlocking, 4000 cubit

diameter circle and square that creates a "Vesica Piscis",

or the "Eye of Horus". Together they comprise the Duat

. The center of this second circle is a very precise location

, exactly 800 royal cubits south of the north east corner

of the Sphinx temple. It is at the base of the vertical

northern face of a hill called Gebel Gibli, this hill

we believe to be the original "mound of creation". The

"Wall of the Crow", or "Southern Causeway", leads to this

place. The measurements from this point offer absolute

conclusive proof that there is something to be found beneath

the sand and debris that has accumulated at the base of

the hill over several millennia. The Giza pyramids form

a mnemonic computer, where the placement of every structure

indicates the next step to be taken in a sequence that

harmonizes and integrates the different geometrys.

At the Spring Equinox sunset of 1998 I stood at the

"Gateway" and watched the shadow of G3A, the easternmost

of the three satellites of Menkaure's pyramid, touch my

feet as the sun disappeared over the western horizon.

That shadow has a measure, it is 1881 cubits long. The

length of the Grand Gallery in the Great Pyramid is 1881

inches . The vertical angle of the Grand Gallery is 26.33

degrees, the angle from the Gateway to the Great Pyramid

is 26.33 degrees, it is the angle generated by the ratio

1: 2, or the angle across a double square. The floor of

the King's Chamber is a double square which measures 10

x 20 royal cubits. Everything on the Giza plateau is commensurate

to a singular system which describes the universe as the

Pyramid Builders saw it and measured it, and then they

constructed their model of the Cosmos with such precision

that the Great Pyramid itself plays a tune, but that we're

saving for our book....

Notes:

1 See Bauval & Gilbert, 1994, The Orion Mystery , London,

William Heinemann Ltd.

2 See Zivie, C.M., 1976, Giza au deuxieme millenaire

, Cairo.

3 See Fraser, The Golden Bough

4 Petrie, W.M.F, 1900, Royal Tombs I, London

5 ibid.

6 Petrie, W.M.F, 1907, Gizeh and Rifeh, London

7 Mariette, 1857, Le Serapeum de Memphis, Paris

8 ibid.

9 Gaballa, G.A., and Kitchen, K.A. 1969, The Festival of

Sokar, Orientalia 38

10 Pyr. 138c

11 For a full discussion of this, see Cox, Pegg, Ritchie, The

Makers of Time, unpublished manuscript

12 Ref from MDAIK 17, 1961

13 Gaballa & Kitchen 1969

14 see Hassan, S, 1946, Excavations at Giza, Vol VI - pt

I, Cairo, Government Press

15 Gaballa & Kitchen 1969

16 Petrie, 1907, pg. 9

17 see Vyse and Perring, Excavations at Giza, 1842

18 Lehner, 1997, The Complete Pyramids, London, Thames

and Hudson

19 So called on a stela of Ramesses III. See Zivie, 1976.

20 See the translation of the Dream stela by Hassan, 1946

21 See Cox, Pegg, Ritchie, The Makers of Time, unpublished

manuscript, for further discussions on this area, notably on

the significance of the positioning of the two modern cemeteries

and the fact that this low lying area could, we believe, be

the legendary 'Field of Reeds', as mentioned in the various

funerary texts.

|